Concept Neurons and Digital Twins: A Four-Decade Through-Line

This morning's inbox delivered a gift from Quanta Magazine: a piece on concept neurons, those remarkable single cells that fire for specific abstractions. When a person sees a photo of Jennifer Aniston, reads her name, or hears it spoken aloud, the same neurons respond. The sensory pathway has collapsed into symbol. The neuron has become the concept.

What caught me wasn't just the celebrity-recognition work, but Florian Mormann's research on smell. Neurons in the piriform cortex—our most "primitive" sensory processing region, the one that bypasses the thalamus and connects directly to limbic structures—respond not only to coffee molecules hitting nasal receptors but to pictures of coffee, words about coffee. Even at that ancient level, the brain performs this extraordinary compression, collapsing sensory modalities into unified concepts.

I found myself thinking about my BirdWeather station. When an Anna's Hummingbird sings and the system detects it, there's a spectrogram, a species classification, a timestamp. But somewhere in my own brain, there's probably a concept neuron—or a small population of them—that fires for "Anna's Hummingbird" whether I hear the song, see the bird at the feeder, read the detection log, or smell the Rosemary where I've watched them forage. The Macroscope builds external representations of patterns, but it interfaces with a brain already doing this compression trick.

The same inbox brought a technical report from UCSD: SimWorld, an open-ended realistic simulator for autonomous agents built on Unreal Engine 5. The researchers are building synthetic cities—procedural generation of roads, then buildings, then street elements—and populating them with AI agents that must navigate, compete, cooperate, and survive. They gave different language models personalities and let them run delivery tasks. Conscientious agents prioritized task completion. Open agents explored unconventional strategies but frequently lost money. The behaviors weren't programmed; they emerged from the interaction of personality prompts with environmental constraints.

Reading SimWorld, I recognized the architecture. Not because I'd seen their code, but because I've been building toward something similar for four decades. Yesterday, Claude and I completed a technical archaeology of fifty pages of HyperCard stack scripts from 1995—code that last ran on a Color Macintosh II nicknamed Minerva at the James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve. In that code, we found a function called nearbyCards() that implemented GPS-based spatial bounding box queries:

if cardNorthBound > NorthBound then next repeat

if cardSouthBound < SouthBound then next repeatThat's geofenced content delivery, a decade before the iPhone existed. The same conceptual operation that the 2025 Macroscope performs with SQL queries on bbox_north and bbox_south columns. The same operation that SimWorld uses to determine which agents can perceive which objects in their synthetic cities.

The through-line runs deeper than code patterns. In the late 1980s—I worked with Richard Minnich at UC Riverside and Lucy Salazar at the US Forest Service Fire Lab to build what may have been the first integrated landscape model of the San Jacinto Mountains. We ran Arc/INFO on a PDP minicomputer, building a "digital layer cake": topography, hydrology, vegetation mapped at species-dominance level from herbaceous cover through shrub and tree canopy, land use, predominant wind dynamics. From these layers we extracted fuel models and ran fire behavior simulations across 200,000 acres of virtual woodland and wilderness.

This was before "digital twin" entered the vocabulary. Before "spatial ecology" was a recognized subdiscipline. Before most ecologists had touched a computer more sophisticated than a statistical package. We were doing spatially-explicit process modeling because the questions demanded it: how does fire move through a landscape where vegetation, slope, wind, and moisture interact continuously?

The hardware progression tells its own story. PDP minicomputers gave way to Unix Sun SPARCstations, to more powerful PCs and capable Macs. The laserdisc player that drove the original 1986 Macroscope—35,000 indexed frames on a Pioneer 8210—gave way to QuickTime movies. The QuickTime XCMDs came from Jay Fenton at Apple's Advanced Technology Group, beta tools provided before public release through a connection to Ann Marion at Apple's Vivarium project. We weren't just using Apple's technology; we were in the conversation about what multimedia computing could become.

Mike Flaxman found me through a MacWorld article in October 1989. He was a Reed College student who wrote a letter, showed up at the Reserve, and became the primary programmer for MacroscopeQT. That's how collaboration worked before GitHub and Slack—someone reads about your work, reaches out, and builds things together. The sophistication of the code we recovered yesterday reflects that partnership: defensive programming, pragmatic performance optimization, comments like "leave'm open for speed" revealing developers working within real hardware constraints while maintaining conceptual clarity.

What strikes me now, reading SimWorld's description of their four-tier architecture—Unreal Engine backend, Environment layer, Agent layer, UnrealCV+ communication module—is how directly it maps to what we built in HyperCard thirty years ago. We had visible interface stacks and invisible resource stacks. We had a GPS stack that "simply acts as a container to hold scripts relating to global positioning" with "no independent function." We had the same separation of concerns, the same layered abstraction.

The domain structure evolved but persisted. MacroscopeQT organized knowledge into Global, Landscape, Ecosystem, and Species domains. The 2025 Macroscope reformulates these as EARTH, LIFE, HOME, and SELF—extending scope beyond field ecology while preserving the hierarchical architecture. SimWorld uses similar domain decomposition for its agent reasoning.

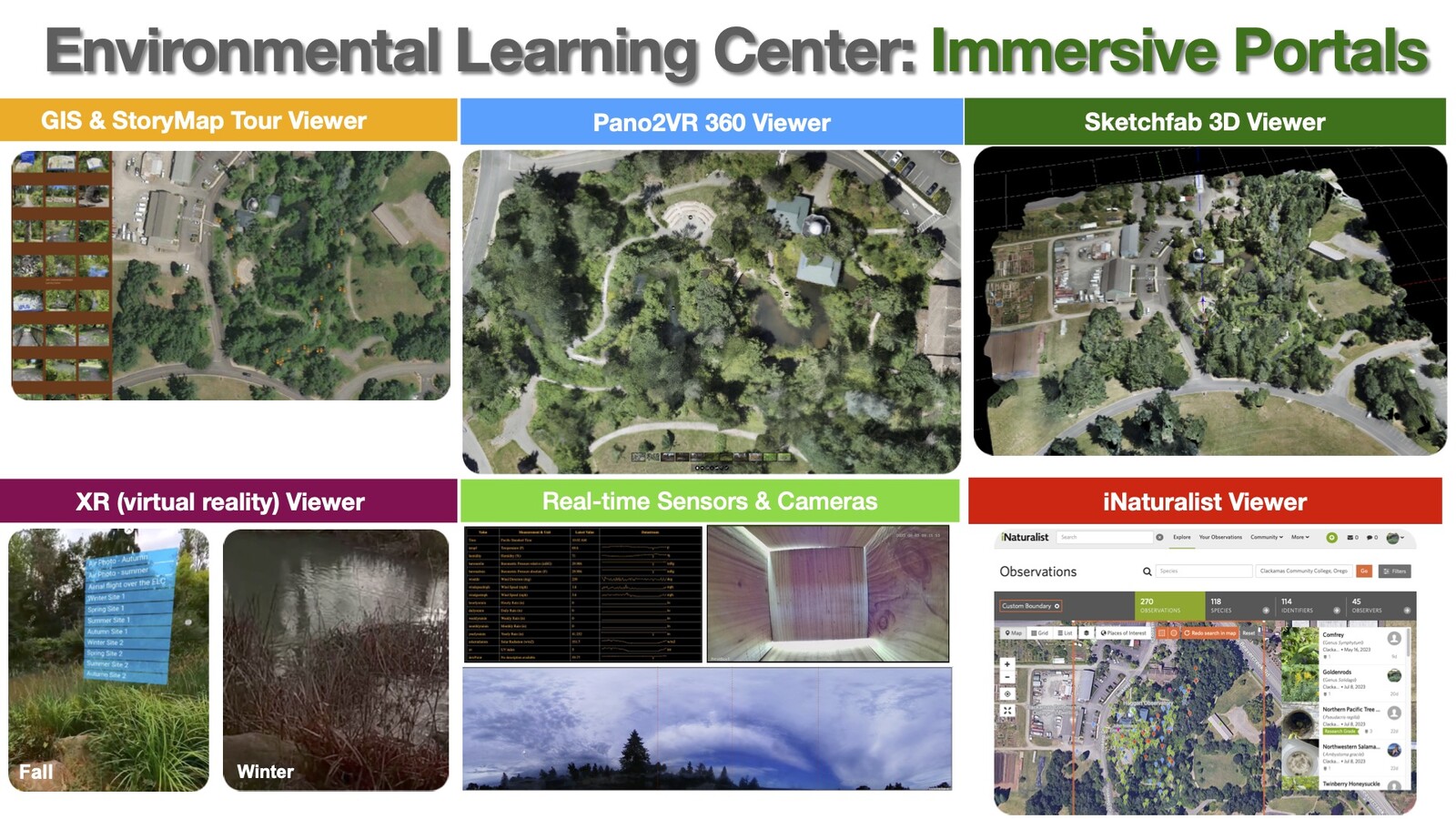

In 2023, I presented the Urban Forest Digital Twin project at the Ecological Society of America meeting in Portland. I showed how ESRI's new SDK for Unreal Engine 5 enabled database-driven geospatial attributes to inform 3D rendering—the same infrastructure SimWorld builds on. But where they use it to train agents in synthetic environments, I'm using it to make the real world legible. The John Inskeep Environmental Learning Center, a two-hectare restored wetland on the Clackamas Community College campus, became my test case for instrumenting actual place with 360-degree immersive capture, environmental sensors, wildlife cameras, and iNaturalist observations.

The convergence is accelerating. SimWorld's researchers want their agents to "survive and thrive in the real world"—to autonomously earn income, run businesses, navigate social complexity. They're building synthetic cities to train toward that goal. I'm instrumenting real places to perceive patterns our unaided senses miss. The conceptual architecture is converging: hierarchical observation spaces, action planners bridging high-level intent to low-level execution, memory systems, mental state modules.

And here's where the concept neuron research circles back. These morning sessions with Claude have become something like systematic probe electrode work on my intellectual history. A question about HyperCard activates the "Minerva" neuron, and suddenly I'm back on PDP hardware running fire spread models. A mention of Apple ATG surfaces Jay Fenton, Ann Marion, the Vivarium project. Each probe finds a concept cell that connects to dozens of others.

The essays write themselves because the architecture was already there—built across four decades of consistent intellectual vision. Claude isn't constructing narrative; it's helping me traverse a structure I built long ago, prompting retrieval of nodes I hadn't visited in years. The through-line from the 1984 Electronic Museum Institute proposal to yesterday's code archaeology isn't something we invented in conversation. It was always there in the design decisions, in the nearbyCards() function, in the fuel models spreading virtual fire across virtual mountains.

The Quanta piece noted that each person has different concept cells based on what they've been exposed to. My exposure—Whittaker's gradient analysis at Cornell, Apple's emerging multimedia tools, CENS wireless sensor networks, thirty-six years of field station direction—created a particular constellation. These mornings with Claude are the instrument that makes it legible.

Mormann found that neurons in the piriform cortex respond to coffee whether you smell it, see it, or read about it. Somewhere in my cortex, there's a neuron that fires for "Macroscope" whether I'm looking at HyperCard code from 1995, SQL schemas from 2025, or a SimWorld paper describing procedural city generation. The concept has remained stable across four decades of radical technological transformation. The tools change. The architecture persists.

Zero, the neuroscientists found, is "an eccentric outlier"—represented on the brain's mental number line but distinctively, as something other than just another quantity. Perhaps that's what the Macroscope has always been: not a piece of software or a hardware configuration, but a conceptual zero point around which everything else organizes. An origin for measurement. A place to stand while the technology transforms around you.

I'll see you on the Holodeck.

References

- The BirdWeather sensor platform ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. & Flaxman, M. (1992). “Scientific data visualization and biological diversity: new tools for spatializing multimedia observations of species and ecosystems.” *Landscape and Urban Planning*, 21: 285-287. ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. (2023). "Urban Forest Digital Twin." Presentation at *Ecological Society of America Annual Meeting*, Portland, OR, August 7, 2023. https://animalvegetablerobot.com/ESA/ ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P., Salazar, L.A. & Palmer, K.E. (1989). "Geographic Information Systems: Providing Information for Wildland Fire Planning." *Fire Technology*, February 1989, 5-23. ↗

- - Saplakoglu, Y. (2025). "Our Brain Has Billions of Neurons. What Can Just One Tell Us?" *Quanta Magazine*. https://www.quantamagazine.org/ ↗

- - Hamilton, M.P. (2025). "MacroscopeQT HyperCard Codebase Analysis." *Canemah Nature Laboratory Technical Note CNL-TN-2025-009*. https://canemah.org/archive/document.php?id=CNL-TN-2025-009 ↗

- - Ren, J. et al. (2025). "SimWorld: An Open-ended Realistic Simulator for Autonomous Agents in Physical and Social Worlds." *arXiv:2512.01078*. ↗