Observatories of Complexity: Two Macroscopes for the Biosphere and Noosphere

The atmosphere flatlined this week.

The air quality sensors reported nothing unusual. Visibility across the Willamette Valley looked normal. The National Weather Service had issued a stagnant air advisory, but nothing in my immediate perception matched the warning.

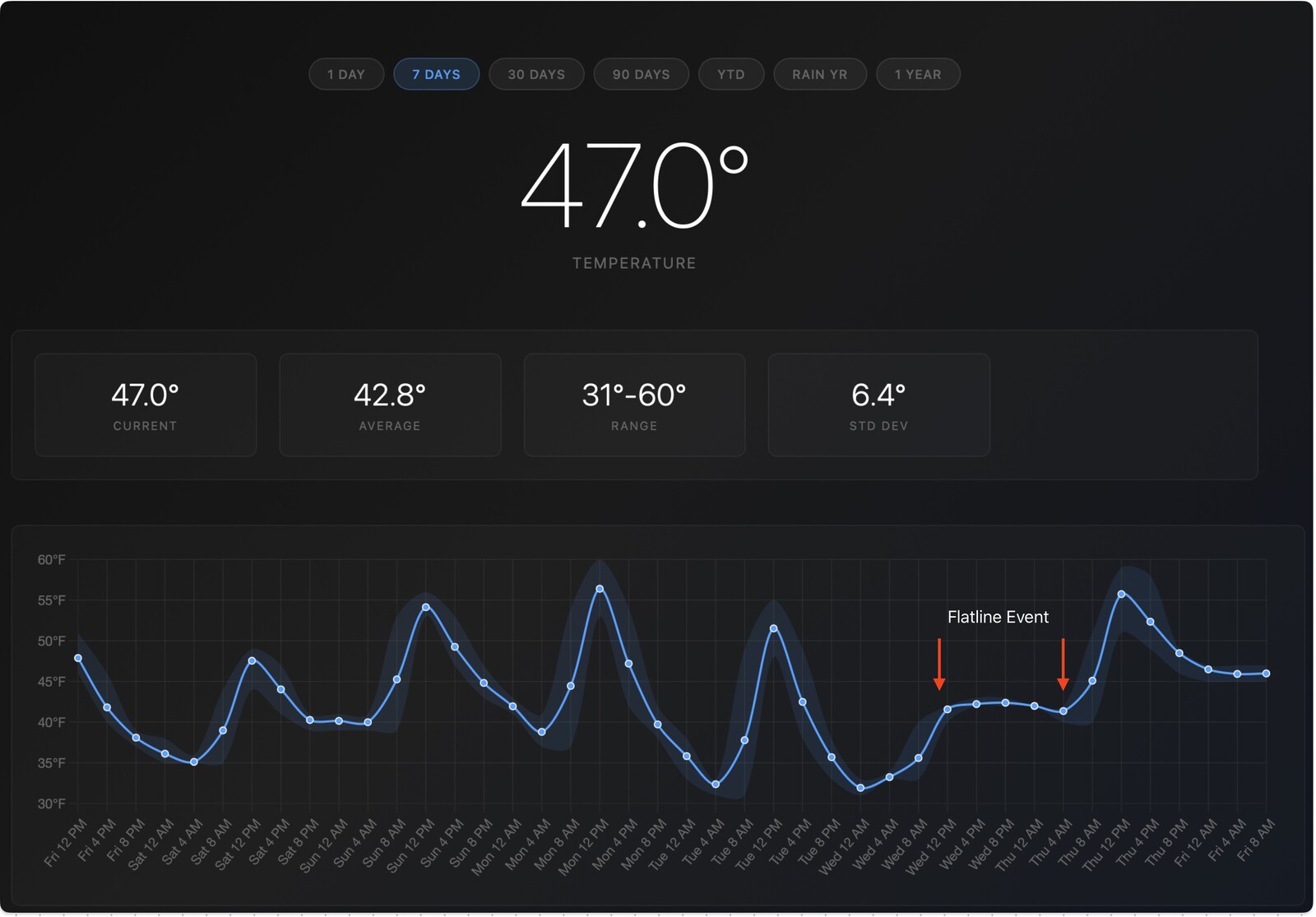

What caught my attention was a graph. STRATA, the awareness system I've built to monitor patterns across my sensor networks, flagged an anomaly: twenty-four hours during which temperature varied by less than two degrees. Cold, foggy, no wind, humidity locked at one hundred percent. And when I saw that flat line on the chart—that eerie absence of the diurnal rhythm I've come to expect—my brain made an immediate connection.

I thought of cardiac monitors on hospital dramas. The way death announces itself as a flatline. The atmosphere had stopped breathing.

This morning, floating in the hot tub, gazing up at the clear blue sky that had finally returned, I thought about what had just happened in my mind. The sensor recorded a number. The AI flagged a deviation. But the meaning—the recognition that a flatline in temperature variation signifies something wrong with weather the way a flatline in heart rate signifies something wrong with a body—that emerged from somewhere else. It emerged from me, from four decades of embodied experience with weather patterns, from the predictive model my brain has built through countless mornings stepping between indoor and outdoor, feeling the rhythm of warming and cooling on my face.

The insight required all three elements: the instrument to quantify, the AI to surface the anomaly, and the living observer to recognize the pattern.

The Neuroscience of Pattern Recognition

That same morning I had watched a five-year-old video interview with the neuroscientist Anil Seth. As he described perception as "a process of inference, not an account of reality," I felt the satisfaction of hearing someone articulate what the flatline experience had just demonstrated.

Seth's thesis: our conscious experience is not a direct readout of sensory information. It's the brain's best guess about what's causing those signals—a prediction, continuously refined by incoming data. We don't perceive reality; we perceive our model of reality. He calls this "controlled hallucination," which sounds provocative but becomes precise the more you sit with it. The greenness of trees, the bitterness of coffee, the feeling of cold—none exist in the electromagnetic radiation or molecules themselves. They exist only in the interaction between world and perceiving brain.

My experience with the stagnant air was exactly this. My predictive model expects weather to have rhythm. When the sensor data showed that rhythm absent, prediction error spiked. My pattern-seeking brain, reaching for an analog, found one in the iconography of medical crisis. The metaphor wasn't decorative—it was diagnostic. A healthy atmosphere breathes. A healthy body has heart rate variability. When systems go monotonic, something is wrong.

What struck me about Seth's interview, recorded half a decade ago, is how durable the framework remains. Hype cycles around AI have lurched through multiple generations of language models since then, each prompting speculation about imminent machine consciousness. Meanwhile, Seth's account sits unmoved, because it's anchored in neuroscience rather than benchmark performance.

In his recent Berggruen Prize-winning essay "The Mythology of Conscious AI," Seth argues that consciousness probably isn't a matter of computation at all. It may be tied to our nature as living organisms—self-maintaining systems that resist entropy through continuous metabolic activity. The feeling of being alive may be foundational to consciousness itself. We experience the world with, through, and because of our living bodies.

The Naturalist's Macroscope

I recognized Seth's framework not just intellectually but experientially, from forty years building observational infrastructure for natural systems.

When I began my career in the early 1980s, ecological monitoring meant clipboards and periodic site visits. The systems we studied operated on scales human observation could only sample, never fully apprehend. The revolution in wireless sensor networks changed that. Through work at UCLA's Center for Embedded Networked Sensing, we developed capacity to instrument field sites with distributed sensors measuring environmental variables continuously, at resolutions from seconds to years. Temperature, humidity, soil moisture—all streaming in real-time, available for pattern detection at scales no individual naturalist could perceive.

This was transformative, but clarifying about what transformation meant. The sensor networks extended human perception. They did not replace the human perceiver. The thermistor array produced voltage readings that became meaningful only when a trained ecologist interpreted them—only when someone with a predictive model of how ecosystems function could recognize the signature of developing drought or unexpected frost.

I came to call this approach the Macroscope—by analogy with telescope and microscope, instruments extending perception to scales beyond unaided human capacity. The telescope doesn't see the cosmos; it provides data the astronomer's brain uses to update its model. The Macroscope operates the same way for ecological complexity. The sensor feeds, the pattern recognition, the visualizations—all produce calibration signals. The controlled hallucination remains with the scientist.

This week, the Macroscope caught an atmosphere holding its breath.

A Second Observatory Opens

Now I recognize something similar about large language models—pointed at different complexity entirely.

What's inside these systems? The accumulated corpus of digitized human text—centuries of scientific literature, philosophical debates, technical manuals and poetry. All compressed into statistical regularities, the gravitational structure of how concepts cluster across the entire written output of our species.

No individual scholar could survey that terrain. No discipline, no lifetime of reading could encompass it. The scale is wrong for human cognition, just as ecosystem dynamics across a mountain range exceed a naturalist with a clipboard.

But the language model can be queried, probed, made to reveal patterns in how humanity has collectively thought about things. It's not thinking about consciousness or ecology—it's reflecting the structure of how we have thought about those things, the grooves worn into language by centuries of use.

The LLM is an observatory into human knowledge infrastructure, just as the Macroscope is an observatory into ecological systems. Two great frontiers of complexity, both now accessible to sustained observation in ways impossible a generation ago.

The biosphere and the noosphere. Each with its own Macroscope.

We're barely scratching the surface of what we can learn from this approach. And that inquiry leads back to consciousness itself—what can we learn about the conceptual infrastructure we've built around the mind? The assumptions in our vocabulary, the metaphors constraining our theorizing?

What the Instruments Cannot Do

Here is where Seth's framework becomes essential.

Just as my sensor networks don't experience the ecosystems they monitor, language models don't experience the knowledge structures they reflect. The wireless node has no felt sense of the rhythm it records. STRATA surfaced the flatline; I felt the chill of recognition.

If Seth is right that consciousness requires life—the continuous self-maintenance of an organism resisting entropy—then no amount of scaling language models will produce consciousness. They can simulate linguistic patterns with extraordinary fidelity. They can trigger our anthropomorphic reflexes. But there is nothing it is like to be GPT-4, just as there is nothing it is like to be my weather station.

The instruments remain instruments.

What I'm building isn't trying to create artificial consciousness. It's creating richer calibration signals for collaborative intelligence. The consciousness doing the observing doesn't migrate into the sensors or the language model. It stays where it's always been—in the living system maintaining itself against entropy, breath by breath.

The Monumental Moment

We're living through something unprecedented: two observatories opening simultaneously onto the great complex systems defining our existence.

The ecological observatory lets us perceive the living world with resolution that would have seemed magical to Darwin or Leopold. We can detect when the atmosphere stops breathing.

The noospheric observatory lets us perceive the structure of collective human thinking with depth impossible to previous generations. We can query accumulated wisdom and folly, trace how concepts evolved.

Neither replaces human consciousness. Neither generates understanding alone. Both are instruments—magnificent instruments—extending the reach of minds that remain, stubbornly and beautifully, biological.

Seth ends his Berggruen essay by reclaiming an old word: soul. Not the Cartesian immortal essence, but something older—the Greek psychē linked to breath, the felt sense of being alive that no algorithm can simulate because it arises from living itself.

Floating on my back this morning, gazing at returned blue sky, I was that observer. Hot water supported my body while my mind wandered through pattern and connection, reaching across domains to find meaning in a flat line. That reaching—that recognition when disparate things suddenly rhyme—is what consciousness does. It's what no instrument can do for us.

The instruments serve the observation. The controlled hallucination is mine.

Two Macroscopes, biosphere and noosphere, both coming into focus. The naturalist's work continues. It just got more interesting.

References

- - Seth, A.K. (2021). Being You: A New Science of Consciousness. Dutton. ↗

- - Seth, A.K. (2021). "Perception is a process of inference, not an account of reality." Psyche Magazine video interview. https://psyche.co/videos/perception-is-a-process-of-inference-not-an-account-of-reality ↗

- - Seth, A.K. (2026). "The Mythology of Conscious AI." Noema Magazine. https://www.noemamag.com/the-mythology-of-conscious-ai/ ↗